RMV Sutton was test driver at Jaguar for only 14 months yet his place in Jaguar history is secure. On 30 May 1949 he drove an XK120 on the Jabbeke-Ostend motorway at 132.596mph. Jaguars had been cad’s cars; now they were classics.

Even for a professional, Belgian National Production Car records were daunting, “I had secret misgivings, bearing in mind my fastest-ever had been 110mph on a Lea-Francis at Brooklands 21 years previously.” Early one morning, Sutton took the XK to a 5-mile straight near Coventry, “It was the car that put my mind at rest as I found it delightful to handle.”

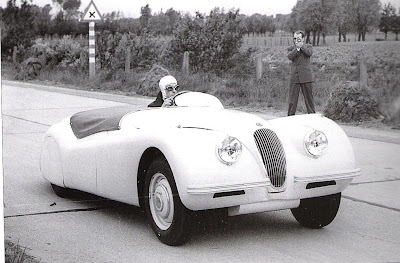

XK120 at Jabbeke. Courteney Edwards, motoring correspondent of The Daily Mail (with cine) was flown to Holland for the occasion.

XK120 at Jabbeke. Courteney Edwards, motoring correspondent of The Daily Mail (with cine) was flown to Holland for the occasion.Roland Manners Verney Sutton (1895-1957) was Jaguar’s chief experimental test driver from February 1948 until April 1951. Norman Dewis took over with a grander title, chief test development engineer, and a wider-ranging brief that included quality and reliability. In Paul Skilleter’s Norman Dewis of Jaguar, Sutton is portrayed as, “unique, with a hangdog look, a cigarette constantly drooping from the side of his mouth. He had aristocratic connections and a Harrow education.”

He certainly had aristocratic connections. Jaguar’s first test driver was a cousin of the Duke of Rutland.

Roland or Rowland (although often referred to as Ron) Sutton was born at Abbots Langley, Hertfordshire into a well-to-do household that included a nurse, housemaid and cook. He was apprenticed to Clayton and Shuttleworth of Lincoln, which made agricultural machinery and steam traction engines. Its chairman Colonel Frank Shuttleworth at age 57 married pretty 23 year old Dorothy Clotilda, a vicar’s daughter of Old Warden, home of the aircraft collection set up by their son, racing driver and pilot Richard Shuttleworth (1909-1940).

RMV Sutton joined Rolls-Royce at Derby in the Operations Planning Department, buying a 1921 sports Hillman for £650. It seemed a lot for, “a primitive two-seater with no starter, screen-wiper or other amenities,” which could barely manage 65mph. He competed in hill-climbs and speed trials against Raymond Mays’s outwardly identical Quicksilver, of which Sutton remarked ruefully, “Judging by the difference in performance its innards must have been modified.”

'Soapy' Sutton, JDHT photograph from Paul Skilleter's Norman Dewis

'Soapy' Sutton, JDHT photograph from Paul Skilleter's Norman DewisFollowing works driver CM Harvey’s victory in a 200-mile race at Brooklands, Sutton exchanged the Hillman for the 1923 Motor Show Alvis 12/50. Works support brought success at Aston Clinton and the car was updated over three years, culminating in an official entry for the 1926 Coupe Boillot at Boulogne. Alvis won the team prize against French factory opposition and Sutton was grateful for competitions department mods that included a high ratio “solid” back axle and Rudge-Whitworth wheels. This improved Brooklands lap times but ruined tyres and he reverted to a differential for hill-climbs. The only preparation required to win the Essex 100-Mile Handicap was removing wings and windscreen.

The Sutton family wealth could not sustain RMV’s motor racing however, so it was with relief that he joined Lea-Francis in 1927 as chief tester and competition driver. Sutton raced the Cozette-blown Meadows 4-cylinder pushrod car, which developed into the production Hyper Lea-Francis that he and Frank Hallam took to an 80.6mph Class F 12-Hour record at Brooklands. Teamed with Kaye Don, George Eyston and Sammy Newsome, they won 1928 Ulster Tourist Trophy.

Sutton’s next job was with Morris Motors Engines Branch at Gosforth Street Coventry Experimental Department. He did road and track tests of the MG Tigress, racing version of the 6 cylinder 18/80 and in a letter to Chris Barker, owner of a surviving Tigress, wrote “I clocked about 95mph at Brooklands, but 100mph, which was the target, eluded us. MG blamed the engine, but we asserted that the bhp was adequate to propel the car at the requisite speed, were it not for losses in the chassis. I made the unfortunate remark, which came to the ears of Cecil Kimber, ‘The engine was contaminated by its surroundings.’ This, I think, put the lid on it, as after two prototypes MG tested the remaining three themselves.”

Sutton raced a Type 40 Bugatti and a Brooklands Riley Nine. In 1932, with CM Harvey, he won the Rootes Cup for leading at the end of the first day of the Junior Car Club’s 100-mile race at Brooklands, yet he found fulfillment testing experimental armoured fighting vehicles, so during wartime moved to Daimler. His Coventry-Climax-engined Triumph road car survived two bombs, but was blown by a third into the drawing office of the Coventry works, rendered roofless by an earlier air raid. The authorities gave him £75 to cover the loss.

The work brought him into contact with the Ministry of Supply, which in 1946 invited Daimler to sample a military Type 82 Volkswagen. Sutton’s report on the captured military Kubelwagen was unflattering, perturbed perhaps by a warning of demolition charges found in Afrika Korps’ cast-offs. A British Intelligence Objectives Sub-Committee pronounced the Volkswagen a design, “of no special brilliance apart from certain details and not to be regarded as an example of first class modern design to be copied by the motor industry.” Sutton was more prescient, “A more refined version of this type might have possibilities.”

Post-war Sutton drove a Rolls-Royce Wraith and Mark VI Bentley, describing them as, “examples of British engineering and craftsmanship that stand supreme.” He ran an electric car, borrowed complete with charging equipment, from the Brush company for several months, “at what I imagined was a negligible outlay, but received a shock of no mean voltage when my electricity bill arrived at the end of the quarter.” He found the acceleration up to 10mph fantastic, “but beyond that it tailed off and the maximum speed was no more than 20mph.” Gradients reduced it to a crawl, the rate of which he was surprised to find never varied no matter whether the incline was 1 in 40 or 1 in 8.

Advertising images: www.car-brochures.eu; Herman Egges collection

RMV Sutton joined Jaguar in 1948, testing tested the 2½ and 3½ Litre saloons with Walter Hassan, moving on to Mark VII prototypes with pushrod engines and then XK120s. Some early development work on the XK was done with the 1½ litre 4 cylinder twin overhead camshaft engine and air-strut suspension, “but it was never the intention of the firm to market this car and only one prototype was built.” Norman Dewis claimed that Sutton’s nickname of “soapy” was the result of his coming to work with shaving cream on his face. Others thought him perpetually begrimed and unwashed, like his overalls.

The reconnaissance trip to Belgium caused consternation. Sutton and Jack Lea, who had known Lofty England and Wally Hassan at ERA, needed to be sure that HKV500 would comfortably exceed 120mph. When they got back they reported to Ernest Rankin, Jaguar’s public relations officer, that it could but Rankin wanted to know why journalists were calling him, asking what Jaguar had been up to in Belgium.

Sutton confessed that they had popped into The Steering Wheel Club, “for a quick one,” on the way home. The clientele of the Steering Wheel, in Brick Street off Park Lane, included journalists and racing drivers. The recce also upset the formidable Joska Bourgeois, Belgian Jaguar importer, who demanded to know why she had not been in on the secret.

Rankin invited journalists on 18th May 1949 to Jabbeke, and on the 30th they flew in a chartered Sabena Douglas DC3 from Heathrow to watch HKV500, chassis number 670002, on the still incomplete Ostend motorway. Painted white to look better in photographs, with a cowl over the passenger seat and undertray to improve aerodynamics, the Royal Belgian Automobile Club timed it over a flying mile and kilometre. To prove this was no fluke it did 126.954mph with windscreen, hood and sidescreens erect.

Accurate, painstaking, fearless yet unassuming according to a tribute in The Motor, RMV Sutton left Jaguar and went back to what he loved, as Chief Development Tester of the Car and Armoured Fighting Vehicle Division at Alvis. He died after a short illness on June 29 1957.

No comments:

Post a Comment