Twenty years ago this week, The Sunday Times motoring column was wide-ranging. Porsche and Volkswagen featured, Kia making it at bottom left on its introduction to Britain, selling 1,786 cars in its first year. Last year it sold 56,114 and has become an international giant making more than 2 million vehicles. Kia Motors Corporation, which celebrated its 67th anniversary in May, began in South Korea manufacturing bicycles, growing to be part of the world’s fourth largest automotive group. Its splendid Scottish Car of the Year Sportage crossover and Sedona MPV are great value for money and recent models such as the European designed and manufactured (if curiously named) cee’d have secured a reputation for quality and reliability.

Yet it is probably Kia's seven year warranty that has been the most distinguished contribution to its success. Peter Schreyer’s appointment as chief designer in 2006 brought the products up to the mark, bringing popularity to new models such as the Soul urban crossover, Venga mini-MPV and new Picanto. Kia has graduated into the mainstream of style; you no longer look on it as a sort of bargain basement car.

Commenting on the anniversary, Michael Cole, Managing Director, Kia Motors (UK) Ltd, said: "Kia has been on quite a phenomenal journey in recent years. In less than two decades we've certainly lived up to our 'Power to Surprise' slogan by growing from a relatively small importer to challenging the best and most established brands in the industry. We think we have a fantastic range of cars and, judging by our growth over the last few years, it seems our customers think so too. 2011 is set to be our busiest year yet and I'm confident it'll be one where we challenge perceptions more than ever as we launch three superb new products in the UK - new Picanto, new Rio and, later in the year, new Kia Optima".

SUNDAY TIMES: Motoring, Eric Dymock

7 July 1991

KIA-PENZA

Two new bargain makes on sale this month offer a practical alternative to buying second-hand. The Escort-sized 1.3 litre Sao Penza will cost under £7,700 and the Metro-sized Kia Pride range is all below £6,800. Both are former Mazdas, the Penza is the old 323 now made in South Africa, and the Kia is the obsolete 121 made in Korea.

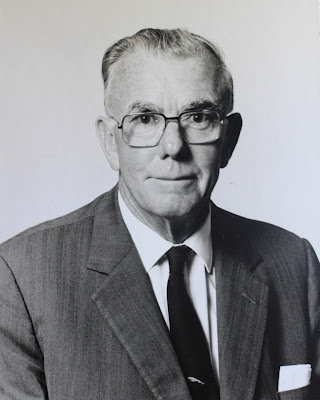

This week's price cuts by manufacturers provide new baselines to try and stem disorderly discounting. Kia and Sao Penza start cheap because they use old technology, yet still come with competitive new-car warranties. They are being imported by MCL Group which sells Mazdas in Britain. Group chairman John Ebenezer, who used to import inexpensive brands from east Europe such as FSO, is optimistic about the new arrivals.

"We are constantly looking for opportunities for new products for the UK market and the improved political situation in South Africa has allowed us to import the Sao Penza." Kia is one of the world's top twenty motor manufacturers although quite a lot of the cars it makes do not carry the Kia brand name. The Pride sells as the Ford Festiva in the Far East.

The most expensive Kia is £1,885 cheaper than the current Mazda 121. The Pride 1.1L 3-door at £5,799, the 1.3LX at £6,399 and the 5-door LX at £6,799 will be among the cheapest superminis on the market.

It hardly matters that Kia's technology is not quite 1991 and the ride and refinement not as good as the Fiat Uno or Nissan Micra. The cars have a useful turn of speed, good economy, an agreeable appearance and seem strongly built.

The two Sao Penza models to be sold here are made by the South African Motor Corporation (Samcor) created in 1985 by the amalgamation of South Africa's Ford and Chrysler operations. Samcor is 76 per cent owned by the Anglo American Corporation and the 5,000 workers own 24 per cent of the shares.

The 1.3 litre five door hatchback will be priced at £7,549 and the four door saloon is £7,695 with metallic paintwork.